![]()

Trachycarpus is a genus of eight species of small and medium size, solitary, dioecious, fan palms, which in the wild grow in an approximate band along the lower Himalayan mountains from northern India, though Nepal, north east India, Burma, China, down to northern Thailand and possibly beyond. Their chief attraction for the grower and palm enthusiast is their cold hardiness and their ease and speed of growth. With the recent discovery of new species, the word 'beauty' could well be added to that list of qualities. For such an easily differentiated genus, there has been a great deal of confusion about the different species which this article will hopefully put to rest; however, it should be stated that ours is a working hypothesis of a classification and not necessarily the last word on the subject.

Originally included under Chamaerops, the genus Trachycarpus (referring to the rough fruits (?)) was established in 1861 by H.A. Wendland. The genus for the most part is historically well-documented. India, Nepal and Burma were British colonies and many an army officer stationed there would spend his spare time studying the local fauna and flora, perhaps disappearing into the hills with a party of 20 or 30 'coolies' for weeks at a time on plant hunting expeditions. Their reports are truly fascinating and have provided valuable clues on our subsequent searches in the same areas. The best historical account of Trachycarpus is, without a doubt, by the famous Italian botanist Odoardo Beccari. His writings are so accurate and precise that they are as relevant today as when they were compiled eighty years ago, and are thoroughly recommended to anyone who would like to know more about the history of this genus. Also worth a look is Myron Kimnach's article in Principes 21:4.

There are eight species in the genus, the seed shape providing a natural sub-division:

A. Those with reniform (kidney shaped) seeds:

|

Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia. Photo courtesy and copyright © 1998, The Pacific Northwest Palm and Exotic Plant Society. |

The first member in the genus to be described, and by a huge margin the most familiar, is Trachycarpus fortunei. It was introduced into Europe (Holland) from Japan in 1830, and subsequently into England, though the most famous introductions there were by Robert Fortune some 20 years later. Mr. Fortune, it would seem, had a much higher profile than the Dutch growers who sent it across the Channel. He had seen the palm growing during his well-documented travels in China and sent some seeds back from the island of Chusan (or Chou-san or Zhousan, as its now known), which lies off the east coast of that country and from which its common name 'Chusan palm' derives. These seeds would have been from cultivated trees. The Chusan palm's hardiness was not realised for a long time and, indeed, the first specimen was grown for many years in the palm house at Kew because it was considered tropical! The early introduced plants fetched a high price, but as more seeds arrived from China the price fell dramatically and it could be said that it has been popular ever since in the UK and elsewhere in Europe.

The first description of this palm was by the Swedish botanist Thunberg who named it Chamaerops excelsa. W. J. Hooker later on described Chamaerops fortunei, which he thought to be a new species, honouring Robert Fortune and based on the material he collected on Chusan Island. As the plant got better known it was placed in its own genus, Trachycarpus, and T. fortunei eventually was considered a synonym of T. excelsa as there were no real differences to separate them. Only much later was it discovered that the herbarium specimens on which Thunberg's T. excelsa was based had been misidentified and actually belonged to a species then called Rhapis flabelliformis. Following the strict international rules of nomenclature, this latter plant had thenceforth to bear the name 'excelsa', making it Rhapis excelsa (even though patently inappropriate for a palm so small), and our palm took the next validly published name, 'fortunei', making it Trachycarpus fortunei. Nurserymen are notoriously slow to accept name changes, however, and many growers (particularly in Europe) still cheerfully sell it under its old name of Chamaerops excelsa.

The 'Chusan palm' is considered to be a native of 'central and eastern' China, but has been so widely cultivated there for thousands of years that its precise origins have long ago been obscured. It is possible that no truly 'wild' trees exist anymore, since so much of the country is under the plough. Its popularity in China is due to the usefullness of the trunk fibres, which are cut from the tree and used for a variety of purposes. We have seen brushes and brooms, doormats, even a crude kind of rain cape (uncomfortably heavy when wet); the latter has largely been replaced nowadays by the lightweight, multicoloured, plastic equivalent but it is still commonly seen in country districts. The tree is so well known it hardly needs any description. Suffice it to say that it has a 10" diameter trunk covered (outside of China anyway) with fibrous old leaf bases, a crown of 3-foot-diameter dark green, fan-shaped leaves with 40 to 50 very irregularly split segments, usually glaucous beneath. The glaucousness is widely variable and should not be taken as an identifying characteristic. The flowers are yellow and on female trees produce, in turn, hundreds of blue/black seeds with a white bloom, which hang down like tiny mis-shapen grapes.

Trachycarpus fortunei is widely planted in temperate and warm-temperate countries worldwide, from Canada to South Africa, from Scotland to New Zealand, and even in the tropics--high up in the mountains of Ecuador and Colombia, for instance. They are easy and rewarding to cultivate; their cold hardiness is legendary; and, like the other members in the genus, they don't need summer heat to grow well (as do so many other cold-hardy palms). Their requirements are minimal. Their main enemy is not cold, but high winds, which will soon damage their leaves. In a sheltered spot or in less windy climates they look their best and are an easy way of bringing a tropical look to the temperate garden.

The seeds germinate without bottom heat in about 8-12 weeks and resultant seedling growth is comparatively fast. Grow them in tubs or, better, plant them out in a wind-free spot when the roots fill an 8" or 10" pot. They appreciate a rich soil, plenty of any kind of fertilizer, and additional water especially in dry areas/seasons. This really can make a huge difference to the speed at which they grow. In favoured localities with regular watering, the Chusan palm can produce a foot of trunk a year and reports of twice this growth rate are probably not exaggerated. Interestingly, growth is fastest at night, and in hot climates Trachycarpus fortunei tends to sulk during the summer months while waiting for cooler weather in which to grow. The only maintenance they require is perhaps an annual removal of dead leaves which, if left in place, can form a 'skirt' in the manner of Washingtonia.

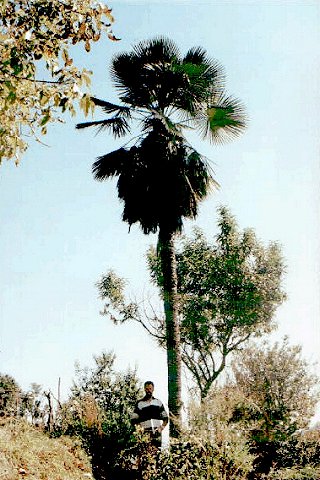

The

rare and only-recently-in-cultivation Trachycarpus

takil, the Kumaon Fan Palm, is closely related to the above. The tiny,

nearly extinct, wild populations are found in Uttar Pradesh province (Kumaon) in central

northern India, where the species grows to 2400 m (8000 feet) and there is a good number

of cultivated trees in the tourist town of Naini Tal there. It is probable that they also

grow across the border in extreme western Nepal, closed, alas, to the independent

traveller. Much confusion has been caused by James McCurrach who, in his 1960 book 'Palms

of the World' (for many years the palm 'Bible') published a photograph of Trachycarpus

wagnerianus with the caption 'Trachycarpus takil'. Thirty-seven years later

confusion still reigns (particularly in the United States) with the two names sometimes

mixed up, and sometimes considered synonymous even though the two species are totally

different in appearance. Trachycarpus takil is a big tree, broadly similar in

appearance to T. fortunei but larger in all its parts, and probably a good few

degrees hardier, thus making it the hardiest in the genus. Sometimes the trunk fibres fall

naturally, leaving a bare trunk. The most obvious differences from T. fortunei

apart from size are the more numerous segments of the leaf (up to 60), which are rigid,

and split the blade to a fairly regular depth, and a curious twist in the leaf next to the

hastula (where the petiole joins the blade). Also, there are differences in the floral

structure. However, it is probably true to say that one of the main differences is

geographical rather than botanical; northern India is, after all, a very long way from

central China.

The

rare and only-recently-in-cultivation Trachycarpus

takil, the Kumaon Fan Palm, is closely related to the above. The tiny,

nearly extinct, wild populations are found in Uttar Pradesh province (Kumaon) in central

northern India, where the species grows to 2400 m (8000 feet) and there is a good number

of cultivated trees in the tourist town of Naini Tal there. It is probable that they also

grow across the border in extreme western Nepal, closed, alas, to the independent

traveller. Much confusion has been caused by James McCurrach who, in his 1960 book 'Palms

of the World' (for many years the palm 'Bible') published a photograph of Trachycarpus

wagnerianus with the caption 'Trachycarpus takil'. Thirty-seven years later

confusion still reigns (particularly in the United States) with the two names sometimes

mixed up, and sometimes considered synonymous even though the two species are totally

different in appearance. Trachycarpus takil is a big tree, broadly similar in

appearance to T. fortunei but larger in all its parts, and probably a good few

degrees hardier, thus making it the hardiest in the genus. Sometimes the trunk fibres fall

naturally, leaving a bare trunk. The most obvious differences from T. fortunei

apart from size are the more numerous segments of the leaf (up to 60), which are rigid,

and split the blade to a fairly regular depth, and a curious twist in the leaf next to the

hastula (where the petiole joins the blade). Also, there are differences in the floral

structure. However, it is probably true to say that one of the main differences is

geographical rather than botanical; northern India is, after all, a very long way from

central China.

Trachycarpus takil was discovered in the 1850’s by a Major Madden, who took it to be T. martianus, thereby forfeiting any claim to fame as its discoverer. He sent seeds and plants to London, from where they were distributed around the United Kingdom and to Ireland, to all the famous nurserymen of the day. A bad move! Who knows what happened to them? Did they grow and mature? Did they hybridize with T. fortunei, itself being more widely grown from that time? Did the seeds of the forbears of the Chusan palms that we grow now come from them? Could it be that in every T. fortunei that we see now in Europe there is some T. takil ‘blood’? Is the twisted hastula that we occasionally see on some present day T. fortunei, some kind of throw-back? Who knows. Perhaps DNA will provide the answer. But even if it has not already done so, T. takil is likely to hybridize easily and readily with T. fortunei, which is a great shame; within

only a few generations of being generally available in cultivation, their special characteristics are likely to be lost, emphasizing the urgent need for serious protection efforts for its remaining wild populations. A hundred years ago there were huge numbers of mature trees up to 12 m in height in the wild. Now they have all been cut down for the fibres.Its requirements in cultivation are identical to those of T. fortunei.

If T. takil is easily confused with T. fortunei,

then Trachycarpus

wagnerianus is not easily confused with anything! Indeed it is

unmistakable, especially when young. It has small, stiff leaves, less than 75 cm (30 in)

across, the leaf segments edged with white wooly fibres. The leaves are so stiff that even

strong winds have no effect on them; thus they are far and away the most suitable palm for

windy sites in the temperate garden. Additionally, they are incredibly beautiful: neat,

tidy, upright, jaunty. Although there is some speculation as to whether it might still

exist in the wild somewhere, in Japan perhaps, hidden on some remote mountain top,

curiously it has never been found and, if wild populations ever existed, they are probably

extinct. The original introductions to the western world came to Italy early this century

when a Mr. Winter bought the entire stock imported from Japan by the German horticulturist

Albert Wagner, after whom he named the species. Despite the name T. wagnerianus

originating from horticulture, differences from T. fortunei were enough to

convince Beccari that it deserved species status and, indeed, it is quite impossible to

confuse it with anything else.

If T. takil is easily confused with T. fortunei,

then Trachycarpus

wagnerianus is not easily confused with anything! Indeed it is

unmistakable, especially when young. It has small, stiff leaves, less than 75 cm (30 in)

across, the leaf segments edged with white wooly fibres. The leaves are so stiff that even

strong winds have no effect on them; thus they are far and away the most suitable palm for

windy sites in the temperate garden. Additionally, they are incredibly beautiful: neat,

tidy, upright, jaunty. Although there is some speculation as to whether it might still

exist in the wild somewhere, in Japan perhaps, hidden on some remote mountain top,

curiously it has never been found and, if wild populations ever existed, they are probably

extinct. The original introductions to the western world came to Italy early this century

when a Mr. Winter bought the entire stock imported from Japan by the German horticulturist

Albert Wagner, after whom he named the species. Despite the name T. wagnerianus

originating from horticulture, differences from T. fortunei were enough to

convince Beccari that it deserved species status and, indeed, it is quite impossible to

confuse it with anything else.

Slow growing and seemingly distorted when young, after 3 to 4 years they literally explode into growth and beauty and, given the rich soil and watering that they need, can double their size every year for a few years, eventually reaching 10 or 20 feet in height, and always retaining those small, unique leaves. Why they are not more common is something of a mystery. Perhaps their slower early growth? The confusion with the names? Whatever the reason, they simply have to become more popular in the next few years as more and more people see how irresistible they are. Just as hardy and as easy to cultivate as T. fortunei, the added benefit of wind resistance will ensure their popularity as soon as they are more widely available.

Equally

unmistakable is Trachycarpus nanus,

the only member of the genus not to grow an above-ground trunk (except rarely and then

only to a foot or so). Native to Yunnan province in China, it is under threat in the wild

due to predation by goats which roam throughout this small plant's entire range. While the

leaves are too tough to eat, the young inflorescense provides a tasty morsel for these

pests which, thus, prevent the plants from reproducing, and since its maximum height is

only 2 or 3 feet, it never grows above the danger level. This interesting small palm

remained in almost total obscurity from 1887, when it was first reported by Father

Delavay, until 1992 when we mounted a small expedition to relocate it (see Principes

37:2, 64-72). A few seeds have subsequently come out of China and it is beginning to

appear in cultivation in Europe and the U.S. It is a pretty species, with very deeply cut,

sometimes green, sometimes blue leaves, their segments numbering not more than 30. Growing

between 1800 and 2300 m a.s.l. (5900 to 7500 ft), it is again very hardy to cold and a

perfect small palm for the temperate garden, although it is slow and initially somewhat

more difficult than most other members in the genus. It requires a very well drained,

heavy soil and a position in full sun to look best.

Equally

unmistakable is Trachycarpus nanus,

the only member of the genus not to grow an above-ground trunk (except rarely and then

only to a foot or so). Native to Yunnan province in China, it is under threat in the wild

due to predation by goats which roam throughout this small plant's entire range. While the

leaves are too tough to eat, the young inflorescense provides a tasty morsel for these

pests which, thus, prevent the plants from reproducing, and since its maximum height is

only 2 or 3 feet, it never grows above the danger level. This interesting small palm

remained in almost total obscurity from 1887, when it was first reported by Father

Delavay, until 1992 when we mounted a small expedition to relocate it (see Principes

37:2, 64-72). A few seeds have subsequently come out of China and it is beginning to

appear in cultivation in Europe and the U.S. It is a pretty species, with very deeply cut,

sometimes green, sometimes blue leaves, their segments numbering not more than 30. Growing

between 1800 and 2300 m a.s.l. (5900 to 7500 ft), it is again very hardy to cold and a

perfect small palm for the temperate garden, although it is slow and initially somewhat

more difficult than most other members in the genus. It requires a very well drained,

heavy soil and a position in full sun to look best.

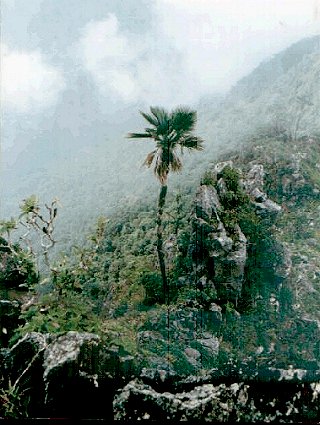

The only species to occur in Thailand is Trachycarpus oreophilus,

the Thai Mountain Fan Palm, which, with a proper botanical description, appeared in the

October 1997 issue of Principes. It grows at some altitude on only one mountain

range, Doi Chiang Dao, in the northwest of the country near Chiang Mai and may possibly

also occur across the border in Burma. The area where it grows at 1700 to 2150 m a.s.l.

(5600 to 7000 ft) is almost continually covered by cloud and mist; it is cool and rather

damp, which makes this another perfect contender for a humid temperate or subtropical

garden. The name 'oreophilus' means 'cloud-loving'. The mountain crests and

ridges where they appear are very exposed and windy from time to time, resulting in much

damage to the leaves. Since there is not a single mature tree in cultivation, we can only

imagine its final, sheltered, appearance for some years to come. It is an exciting

prospect! The wild trees have a slim, naked trunk, caused by the very short fibrous

leaf-bases soon falling, a compact, broader-than-deep, hemispherical crown of leaves,

these regularly split into 60 or more segments and self-shedding on dying. So far, with

the possible exeption of T. nanus, it has proven to be the slowest of all the

species in cultivation, taking several years to put out its first divided leaf, though

perhaps it will speed up once established. A rich but well drained soil is recommended.

The only species to occur in Thailand is Trachycarpus oreophilus,

the Thai Mountain Fan Palm, which, with a proper botanical description, appeared in the

October 1997 issue of Principes. It grows at some altitude on only one mountain

range, Doi Chiang Dao, in the northwest of the country near Chiang Mai and may possibly

also occur across the border in Burma. The area where it grows at 1700 to 2150 m a.s.l.

(5600 to 7000 ft) is almost continually covered by cloud and mist; it is cool and rather

damp, which makes this another perfect contender for a humid temperate or subtropical

garden. The name 'oreophilus' means 'cloud-loving'. The mountain crests and

ridges where they appear are very exposed and windy from time to time, resulting in much

damage to the leaves. Since there is not a single mature tree in cultivation, we can only

imagine its final, sheltered, appearance for some years to come. It is an exciting

prospect! The wild trees have a slim, naked trunk, caused by the very short fibrous

leaf-bases soon falling, a compact, broader-than-deep, hemispherical crown of leaves,

these regularly split into 60 or more segments and self-shedding on dying. So far, with

the possible exeption of T. nanus, it has proven to be the slowest of all the

species in cultivation, taking several years to put out its first divided leaf, though

perhaps it will speed up once established. A rich but well drained soil is recommended.

The

adventure of our discovery of Trachycarpus

princeps, the Stone Gate Palm, can be read in Pricipes 39

(2):65-74. It grows near to where the borders of China, Tibet and Burma meet, politically

something of a hot-spot. What the Principes article doesn't tell is that the

previous year we had made an 'unofficial' attempt to get there. This whole area of China

is closed to foreigners and with our height and obvious Western appearance, we stood out

like sore thumbs. Nonetheless, we hitch-hiked successfully west from Kunming as far as the

Mekong River which we crossed by a footbridge. Ahead of us lay an over 4000 m high

mountain range and since there appeared to be no road crossing it we had no alternative

but to climb it ourselves, in the company of three Chinese peasants who offered to guide

us, for a fee, which increased with the altitude.

The

adventure of our discovery of Trachycarpus

princeps, the Stone Gate Palm, can be read in Pricipes 39

(2):65-74. It grows near to where the borders of China, Tibet and Burma meet, politically

something of a hot-spot. What the Principes article doesn't tell is that the

previous year we had made an 'unofficial' attempt to get there. This whole area of China

is closed to foreigners and with our height and obvious Western appearance, we stood out

like sore thumbs. Nonetheless, we hitch-hiked successfully west from Kunming as far as the

Mekong River which we crossed by a footbridge. Ahead of us lay an over 4000 m high

mountain range and since there appeared to be no road crossing it we had no alternative

but to climb it ourselves, in the company of three Chinese peasants who offered to guide

us, for a fee, which increased with the altitude.

We began with much enthusiasm and energy, losing both after we'd been going for a few hours. That first night we slept, exhausted, in a hovel surrounded by a sea of mud in which cows and goats were pissing and children were playing. The next day we continued upwards through different zones: a thicket of dense bamboo, a forest of tree-like Rhododendron on mossy ground, a beautiful wetland area with stunted, almost bonsai-like conifers, a broad band strewn with rocks the size of car engines. A second night in another hovel, an early start and we headed again towards the summit. Emerging above the tree line we came onto a grassy meadow, in which were growing thousands of Gentians of the most intense blue. By the time we actually reached the summit at 3900 m, we were so tired we were almost hallucinating; it really was the most physically exerting thing either of us had ever attempted. Down the other side then, our legs feeling like rubber.

Soon after beginning our descent we were stopped by an aggressive young man in military uniform, who burst out of a hut. He spoke no English but the word 'passport' cropped up in his speech. If we were alarmed by this turn of events, our guides were terrified, especially when we began handing over money to ease our passage. When we had paid over about $20 he angrily waved us on our way, and for a few hundred yards we even forgot our tiredness as we sped down that mountain track! That night, we finally we made it down to the valley bottom, crossed the Salween River by footbridge and sneaked into a small town. Our attempts to maintain a low profile proved useless; we were soon surrounded by the entire population, most of whom had never seen a European before. So remote was this town that the police officer there didn't realize that we were seriously off-limits and the next day, simply helped us on our way. At that point though, our luck ran out. Forty miles up the road, so close to our goal, we were arrested for real and sent, with a police escort, all the way back to civilization. Back in Europe, we had to wait a whole year while our official application was considered, and, on payment of $2000 for 'logistical support' we were allowed up there again, in the company of a Chinese professor and an interpreter. Finally, we found our palm.

Perhaps the most beautiful of the genus, the backs of the leaves of Trachycarpus princeps are covered with a pure white waxy substance, thick enough to be scratched off with a finger nail and which easily differentiates it from its closest relatives. It grows in an area of incredible natural beauty in a deep gorge on the cliffs of a 1000-foot-high split in the mountain range, which the Salween (Nu Jiang) River has cut out of the marble stone. We were unable to find any seeds, and since further attempts to visit the site seem to be quite impossible, it is unlikely that this beautiful species will find its way into cultivation just yet. From time to time seeds of 'T. princeps' have appeared in seed dealers' lists. These are NOT the real thing (some are not even reniform) and should be avoided. We can say with some confidence that no seeds of this species have ever been brought out of China to this day.

B. Those with oval-and-grooved seeds:

Trachycarpus martianus

can be seen at a few botanic gardens around the world: Huntington, Sydney, Kew; but it is

by no means commonly encountered. Most reports of this palm turn out to be T. fortunei

with a bare trunk! This is not, I repeat NOT, a distinguishing characteristic. The splits

in the leaves, very regular in this species, while irregular in T. fortunei, and

the leaf segments numbering 65 to 75, occasionally up to 80 are a much more reliable

guide. This, together with the seed shape, means they should really never get confused.

Trachycarpus martianus

can be seen at a few botanic gardens around the world: Huntington, Sydney, Kew; but it is

by no means commonly encountered. Most reports of this palm turn out to be T. fortunei

with a bare trunk! This is not, I repeat NOT, a distinguishing characteristic. The splits

in the leaves, very regular in this species, while irregular in T. fortunei, and

the leaf segments numbering 65 to 75, occasionally up to 80 are a much more reliable

guide. This, together with the seed shape, means they should really never get confused.

It is distributed in two far-apart areas, one in central Nepal, one in Meghalaya Province (and possibly also further east) in India, separated by several hundred miles. At one time they were thought to be separate species, the eastern population having originally been described as 'T. khasianus', but, though there are some subtle differences, they seem basically the same. The Nepal form grows at considerably higher altitude and should prove to be somwhat hardier to cold. They are rather beautiful palms, slim, elegant, with neat crowns of fine, fan shaped leaves, as stated above, regularly divided and with numerous segments. The petioles are covered with a white tomentum--tiny white fibres--giving the petiole a slightly hairy appearance.

As with T. oreophilus, the places where they choose to grow in the wild are rather exposed and windy. Cultivated plants look quite different and would sometimes hardly seem to be the same species. Seedling growth is reasonably fast and since seeds are now more frequently available there is no reason why this beautiful palm should not, in a few years' time, be gracing the garden of every temperate palm enthusiast.

Trachycarpus martianus was reported as growing on limestone hills but, contrary to this, we have actually found them growing on highly acidic soils. This may be why they are sometimes reported as difficult to grow. Frustrated enthusiasts should maybe change the pH of their soil and try again. Young plants enjoy cool, humid conditions out of full sun.

Photo courtesy and copyright © 1998, Ganesh Villa Pradhan, The Orchid Retreat; Kalimpong, West Bengal, India. |

Only recently described, Trachycarpus latisectus, the Windamere Palm, was previously known as T. 'sikkimensis' and many thousands of seeds have been distributed under that name, which was used as a working title but is now invalid and should not be used. 'Latisectus' refers to the broad leaflets, indeed one of the distinguishing characteristics of this palm, which are around 5 cm (2 in) wide, very glossy, and of which there are around 70 in total, forming a very large and leathery leaf. It has a bare trunk and its seeds resemble those of T. martianus. Remaining in the wild in just one tiny, heavily altered location in the Sikkim Himalayas in north-east India, which is immediately threatened by destruction, it has only recently been introduced into cultivation, but is about to make a huge impression in the palm world. It is so big and bold, so distinctive, so cold-hardy, and so beautiful, it should, by rights, leave T. fortunei standing, in the popularity stakes. Also, it is probably the only species in the genus which, owing to its wide altitude range from 1200 to 2400 m (3950 to 7900 ft), will adapt well to hotter regions.

Seedling growth is slightly slower than the Chusan palm but speeds up as the young plants get bigger. As with the preceeding species, spider mites seem irresistably attracted to it and steps should be taken to prevent them getting a hold on the young plants. As yet, there are no even middle-sized plants outside its native land, so cultivation experiences out of India are necessarily limited to plants only a few years old. As with other Trachycarpus, T. latisectus requires a rich, loamy but well drained soil. Young plants are best grown under some shade.

That's the full complement. But what about the suckering species you may ask? In our opinion, it doesn't exist. Sometimes in palms there is mutation, variegated leaves say, or simple instead of divided leaves, and individual plants may (rarely) grow several stems like a seedling T. takil we found in which the growing point bifurcated. This does not represent a distinct species however. We have also seen individuals of T. fortunei branching above ground, a curious reaction caused by damage to the growing point which has been observed likewise in many other palm genera. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for a Trachycarpus fortunei to appear to develop a side shoot but this is, in fact, the main growing point emerging from the side of the plant because the way up is blocked for some reason, possibly the result of some damage. Once this establishes itself, the original main 'stem' will die back. If it is removed, the plant may well go on to produce another, but it is still the one and only growing point seeking a way out and up. One grower removed 4 such from a T. fortunei as he wanted a single trunk! As soon as one was allowed to develop, the main 'stem' died. Others that are 'clustering' are simply the result of several seeds being planted together. On every such specimen we have examined, including the type specimen of T. fortunei var. 'surculosa', all the trunks are the same age (a bit of a giveaway that) and invariably both sexes are represented, impossible with a truly clustering palm. However, we would be delighted to be proven wrong.

The future.

One of the most significant things about several species of Trachycarpus that we have studied in the wild is the tiny size of their populations, in terms of either area or numbers. All the species apart from T. fortunei are more-or-less seriously threatened, some close to extinction in the wild. Trachycarpus takil, T. princeps, T. oreophilus and T. latisectus all grow in very small populations or areas that could so easily be missed were they not known about. You could pass within five hundred yards of some of them and not even dream that they were there. While this may be frustrating, it also has an exciting aspect to it. There may well be several more species just waiting to be discovered perhaps in areas apparently well documented. Northern Burma, for example, could be home to existing or even new species, but we will not know until the dreadful regime there falls and we can go and look for ourselves. The band along which most species grow seems to peter out towards north Vietnam. An expedition there may well turn up some interesting discoveries. Since we became interested in this genus we have discovered three new species along the Trachycarpus Trail. Who knows where it may lead next?

| Martin Gibbons The Palm Centre Ham Central Nursery - Ham St., Ham Richmond, Surrey, TW10 7HA United Kingdom Tel ++44 181 255 6191 Fax ++44 181 255 6192 |

Tobias

W. Spanner Palme Per Paket Tizianstr. 44 80638 Muenchen Gemany Tel ++49 89 1577 902 Fax ++49 89 1577 902 |

Note: This article was originally published in the Palm Journal and is reprinted here with permission from the authors. All photos (except those wtih copyright and location information given) are copyright © 1998, Martin Gibbons and Tobias W. Spanner; most were taken in habitat.

![]()

| PACSOF Home Page | |||

| Virtual

Palm Encyclopedia Site Map Powered by FreeFind. |

|||

This site is copyrighted © 1998, 1999, 2000, Palm & Cycad Societies of

Florida (PACSOF)

For questions or comments, e-mail the webmaster.

Internet hosting provided by Zone 10,

Inc.